Professor Pierre Buffet’s research unit (UMRS 1134, Inserm Université Paris Cité), in close collaboration with the team of Professor Chrétien at Institut Pasteur, and an Australian-Indonesian team led by Professor Nick Anstey, observed in patients with chronic malaria a concentration of infected red blood cells 20 to 4000 times higher in the human spleen compared to circulating blood. These results suggest that key stages of the parasite cycle occur predominantly in the spleen, thereby altering significantly our understanding of malaria.

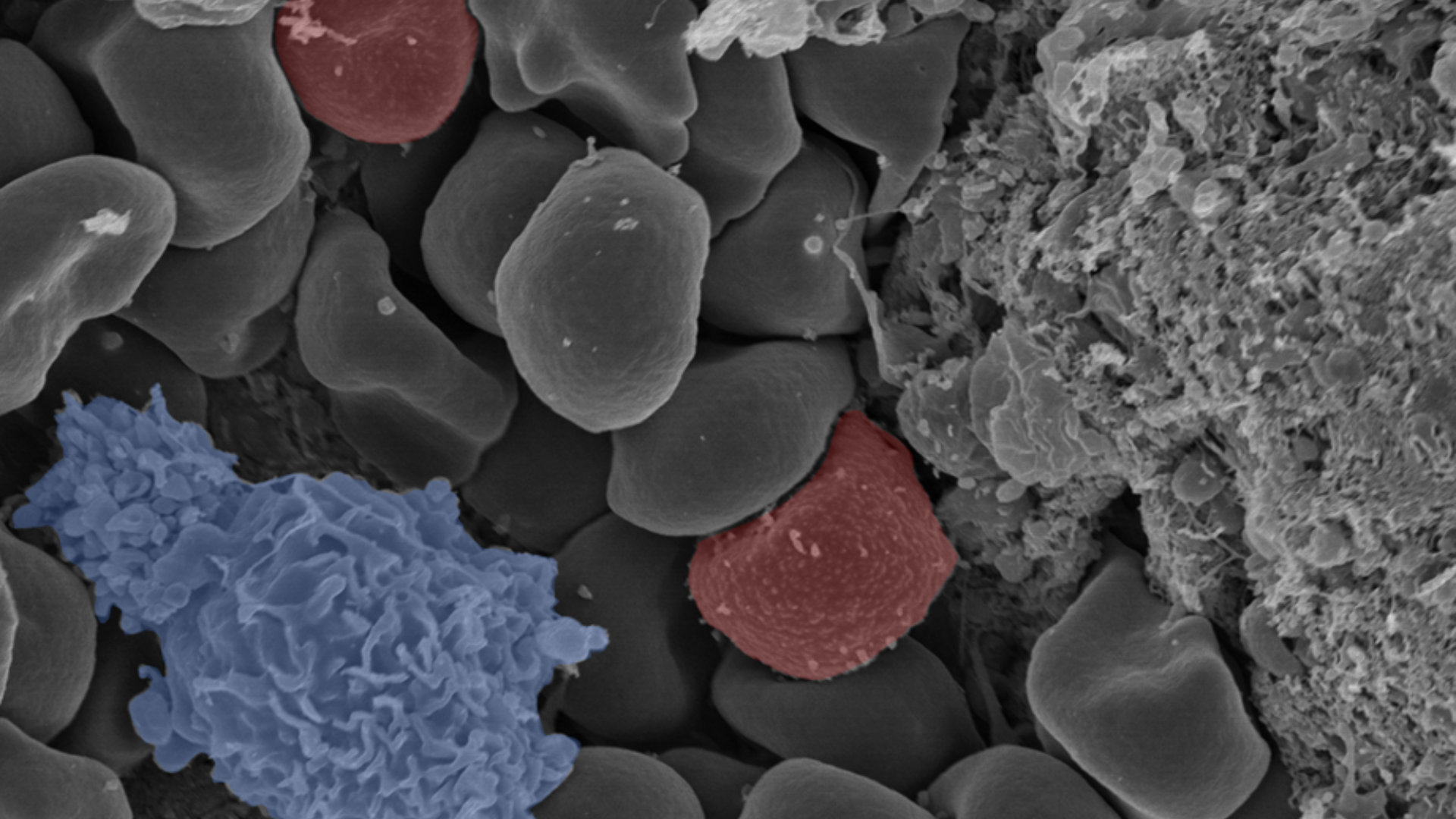

Parasitized red blood cell (red) in a human spleen in the middle of normal red blood cells. (White blood cell in blue)

© Pierre Buffet

Malaria is a potentially fatal infectious disease caused by several types of microscopic parasites belonging to the genus Plasmodium. Transmitted to humans by an infected mosquito bite, the parasite settles and multiplies in red blood cells, then bursts them. It can then spread and infect more and more red blood cells.

In areas where malaria is actively transmitted, some individuals, named chronic carriers, may sustainably carry parasites during long periods of time without having any symptoms related to the infection. In these areas, many children and some adults have an abnormally enlarged spleen (splenomegaly).

The spleen initiates immune responses against blood-borne microbes, and also filters the blood to destroy and eliminate abnormal or infected red blood cells. The abnormally large spleen in chronic parasite carriers is due in part to the accumulation of red blood cells that have been altered by the infection and are pooled in the spleen then destroyed and eliminated. This function of eliminating abnormal blood cells is generally beneficial but not devoid of side effects. In fact, the spleen retains infected or altered red blood cells causing the proportion of red blood cells in the circulating blood to decrease sharply, leading to severe or even fatal anemia, especially in infants.

In Papua Indonesia, the researcher Steven Kho (first author of the paper) collected human spleen fragments as a result of emergency surgeries performed after road accidents. Examination of these spleen fragments, using methods validated on human spleens experimentally infected in France, showed that almost all of the individuals, even though they had no symptoms of malaria, were parasite carriers. Moreover, the concentration of infected red blood cells was 20 to 4000 times higher in the human spleen than in the circulating blood. Some individuals had many parasites in the spleen but none in the bloodstream. Moreover, some of the parasites collected from these fragments could be propagated in laboratory culture system and were therefore alive at the time of sampling. This major observation indicates that the spleen would not only be the place of destruction and elimination of infected red blood cells but also a safe haven for the long-term persistence of the parasite. This would explain in part the difficulty in eliminating certain types of this parasite, in particular Plasmodium vivax that predominates in Asia and Latin America.

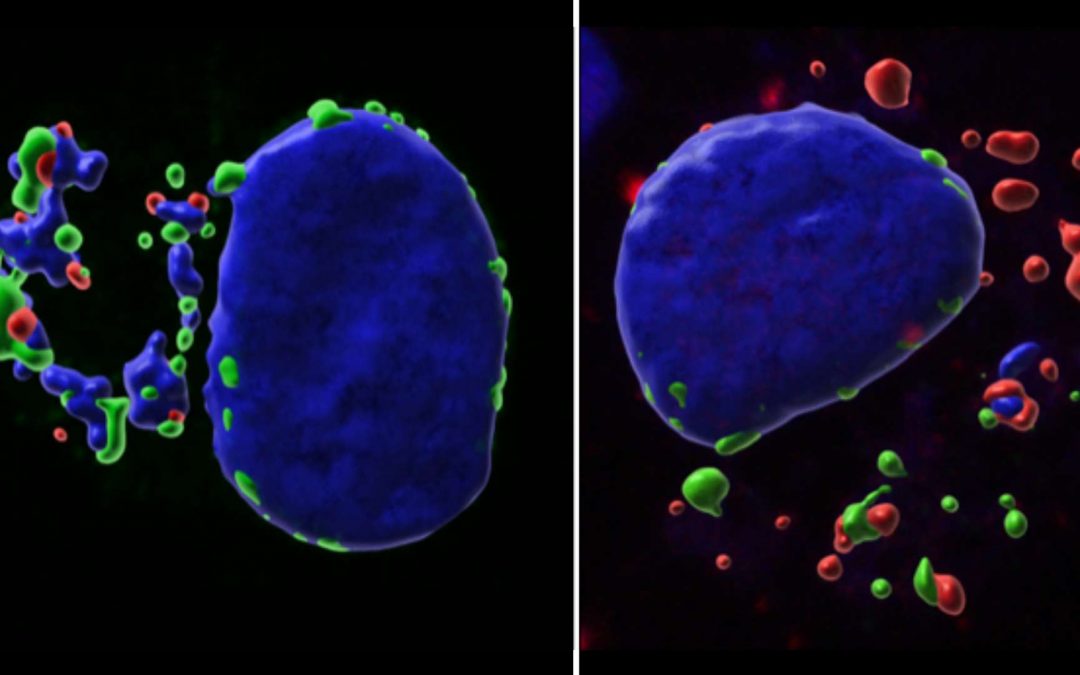

Plasmodium vivax develops exclusively in young red blood cells (reticulocytes). Analysis of human spleens by the same research teams demonstrated that, in addition to the accumulation of parasites, there is also an accumulation of reticulocytes in the human spleen. These results indicate that once reticulocytes leave the bone marrow where they are produced, they stay in the spleen before reentering the bloodstream. In the spleen of individuals who are chronic parasite carriers, reticulocytes are therefore in close proximity to red blood cells infected by the still living parasite. A significant proportion of these reticulocytes are then infected by the parasite before entering the circulating blood and ultimately spreading the infection in the population via the mosquito. Therefore, it seems that most of Plasmodium vivax life cycle actually takes place almost entirely in the spleen, where the parasite finds the young red blood cells it needs to persist and multiply.

These observations change the general view of malaria infection, which should now be considered more as an infection of the spleen than an infection of the circulating blood.

References

- Hidden Biomass of Intact Malaria Parasites in the Human Spleen .

Kho S, Qotrunnada L, Leonardo L, Andries B, Wardani PAI, Fricot A, Henry B, Hardy D, Margyaningsih NI, Apriyanti D, Puspitasari AM, Prayoga P, Trianty L, Kenangalem E, Chretien F, Safeukui I, Del Portillo HA, Fernandez-Becerra C, Meibalan E, Marti M, Price RN, Woodberry T, Ndour PA, Russell BM, Yeo TW, Minigo G, Noviyanti R, Poespoprodjo JR, Siregar NC, Buffet PA*, Anstey NM

*.

N Engl J Med. 2021 May 27;384(21):2067-2069. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2023884. PMID: 34042394.

* Contributed equally

- Evaluation of splenic accumulation and colocalization of immature reticulocytes and Plasmodium vivax in asymptomatic malaria: A prospective human splenectomy study. Kho S, Qotrunnada L, Leonardo L, Andries B, Shanti PAI, Fricot A, Henry B, Hardy D, Margyaningsih NI, Apriyanti D, Puspitasari AM, Prayoga P, Trianty L, Kenangalem E, Chretien F, Brousse V, Safeukui I, del Portillo HA, Fernandez-Becerra C, Meibalan E, Marti M, Price RN, Woodberry T, Ndour PA, Russell BM, Yeo TW, Minigo G, Noviyanti R, Poespoprodjo JR, Siregar NC, Buffet PA*, Anstey N*.

* Contributed equally

Malaria is a potentially fatal infectious disease caused by several types of parasites belonging to the genus Plasmodium. The parasite, which settles in red blood cells, is transmitted to humans an infected mosquito bite. This disease affects around hundred countries in the world, notably in the poor tropical areas of Africa (90% of cases), Asia and Latin America. Approximately 40% of the world’s population is exposed to the disease and 500 million clinical cases are reported each year. There are more than 400,000 victims per year in the world. The situation is even more alarming as the parasites have been developing resistance to antimalarial molecules for several years and mosquitoes are becoming less sensitive to insecticides. Today, no vaccine is widely available but molecules such as atovaquone-proguanil, doxycyline, artemisinin-based combination therapies can be used for both prevention and treatment. In regions where malaria is highly endemic, some individuals, after many years of chronic infection by the parasite, tolerate its presence and develop a natural immunity. The adaptation mechanisms of the parasite in humans remain poorly understood. At the same time, individuals with little or no symptoms of malaria may remain parasite carriers for a long time, which complicates the elimination of the disease.

Pierre Buffet

PU-PH de Biologie cellulaire, Faculté de Santé, Université Paris Cité

UMRS 1134 – Inserm – Université Paris Cité

Institut National de la Transfusion Sanguine

Read more

Theileria annulata and Cancer: a parasite strategy revealed!

A new study from Prof. Jonathan Weitzman’s research team at the Epigenetics and Cell Fate unit has shed light on the mechanism by which the parasite Theileria annulata, which causes a cancer-like diseases in cattle, evades the host cell’s defense mechanism.

Université Paris Cité commits to Planetary Health

Bold ambitions driven by optimism characterise Université Paris Cité’s new initiatives, supported by its president Édouard Kaminski. In 2024, Kaminski announced the university’s new focus for the next five years, summed up by its motto: “Planetary health: healthy...

Paris-Oxford Partnership (POP) Annonces its Results

The Paris-Oxford Partnership (POP) Evaluation Committee, composed of Université Paris Cité, CNRS, Institut des Etudes Avancées and Oxford University, announces the results of its calls for projects. The call aimed to facilitate and strengthen scientific collaborations...

International Students: Anticipate your start at the university!

Welcome to Univesité Paris Cité ! The Student Life department provides assistance for preparing your arrival in France and supports you throughout the entire year. You have been admitted or are a new international student...