A short story by by Katelin Marit Parsons (University of Iceland)

My grandmother had no memory of the book that I found in her basement when I was fifteen years old. The elaborate handwritten title-page declared that it was the property of Emma Millard.

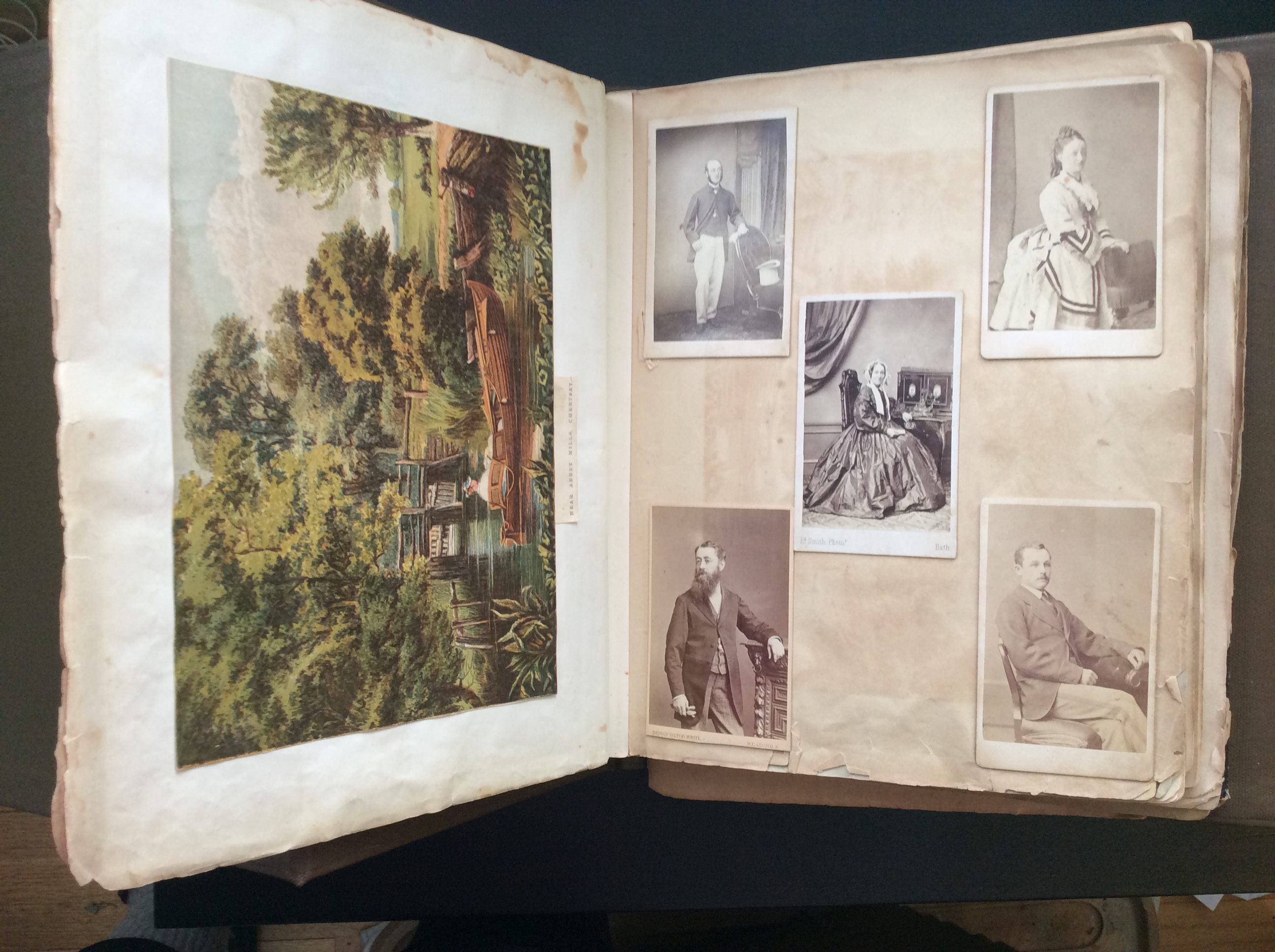

Inside, the book concealed a treasure trove of Victorian photographs, handwritten poems, brightly tinted engravings and drawings: a precious visual archive of an entirely unknown life. Judging by the book’s condition, this album was one of Emma’s most prized possessions. The album captures the life of a woman on the move: from Bath in England to a rural Anglo-Canadian community in York County, Ontario.

The first clue that Emma’s album had a family connection were sketches signed by Olivia Smith, my great-great-great-grandmother. My grandmother recalled that Olivia had immigrated to Canada from England as a young single woman in the mid-nineteenth century and married an Ontario tavern-keeper, Joshua Sisley. Judging by the album, Emma made the same Atlantic crossing but remained single all her life.

The first clue that Emma’s album had a family connection were sketches signed by Olivia Smith, my great-great-great-grandmother. My grandmother recalled that Olivia had immigrated to Canada from England as a young single woman in the mid-nineteenth century and married an Ontario tavern-keeper, Joshua Sisley. Judging by the album, Emma made the same Atlantic crossing but remained single all her life.

Olivia Smith Sisley and Emma Millard are buried in the same grave in Richmond Hill Presbyterian Cemetery, together with Olivia’s husband, mother-in-law, sister-in-law and two of Olivia’s children. Emma’s grave gives her birth year as 1835 and her death year as 1893.

I lost my grandmother when I was sixteen, before the mystery of the album could be solved. In the many years that have passed since then, I’ve spent most of my research hours prying into the lives and manuscripts of complete strangers.

The COST Action Women on the Move has been an inspiration to reconnect with a story close to home. Who was Emma Millard, and what can her album tell us about her migration experience? Beyond her album, we have only a gravestone in Toronto and a handful of census records.

The exact year that Emma Millard and Olivia Smith left England for Canada is unknown, but Emma’s album suggests a date in the early 1850s. By this time, Olivia was a young woman in her twenties, but the younger Emma was still probably only a teenager.

Emma bought her book at the shop of printer and engraver Joseph Hollway, located at 10 Milsom Street in Bath. Milsom Street was lined with shops and a popular destination for visitors to the city. The building today stands only a few metres from the Jane Austen Centre, a museum dedicated to the novelist’s years in Bath in the early nineteenth century.

Austen’s final novel, Persuasion (1817), describes the chance meeting of an admiral and a baronet’s daughter outside of a Milsom Street printshop. That Emma was able to buy her album on a fashionable Bath shopping street suggests that she was not a destitute young woman. Nevertheless, Emma did not belong to a social class of women who could afford to cross the Atlantic Ocean at a whim. Whether she was motivated to emigrate by friendship, kinship, an adventurous spirit or a practical concern for her future, it would have been clear to Emma that this was a one-way journey. This knowledge must have motivated the creation of an album preserving familiar landscapes and faces from her home country.

Austen’s final novel, Persuasion (1817), describes the chance meeting of an admiral and a baronet’s daughter outside of a Milsom Street printshop. That Emma was able to buy her album on a fashionable Bath shopping street suggests that she was not a destitute young woman. Nevertheless, Emma did not belong to a social class of women who could afford to cross the Atlantic Ocean at a whim. Whether she was motivated to emigrate by friendship, kinship, an adventurous spirit or a practical concern for her future, it would have been clear to Emma that this was a one-way journey. This knowledge must have motivated the creation of an album preserving familiar landscapes and faces from her home country.

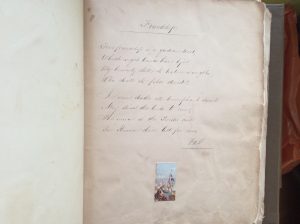

The album’s entries suggest a well-planned but emotional departure from England. Rather than writing personal messages addressed directly to Emma, her unknown friends, acquaintances and loved ones hand-copied poems directly into the album that they felt would speak appropriately to the situation and their emotions. “True friendship is a Gordian knot” and “When shall we three meet again” are the poetry of a final farewell. By contrast, Longfellow’s popular “Tell me not in mournful numbers” is an encouragement to the young emigrant to be unafraid “to act, that each to-morrow / find us farther than to-day” and leave behind her “footprints on the sands of time.” Unlike a migrant’s personal diary, the album is a collectively created object, documenting multiple voices and perspectives on the migrant experience.